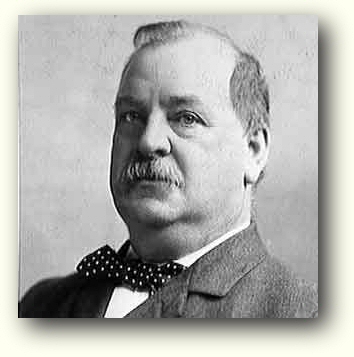

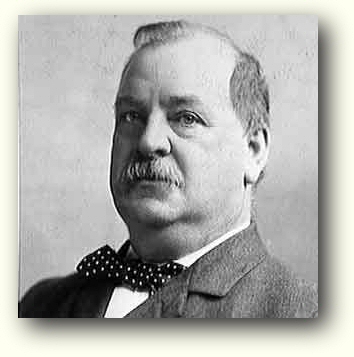

Grover Cleveland

Grover Cleveland

22nd President 1885-1889 and 24th President 1893-1897

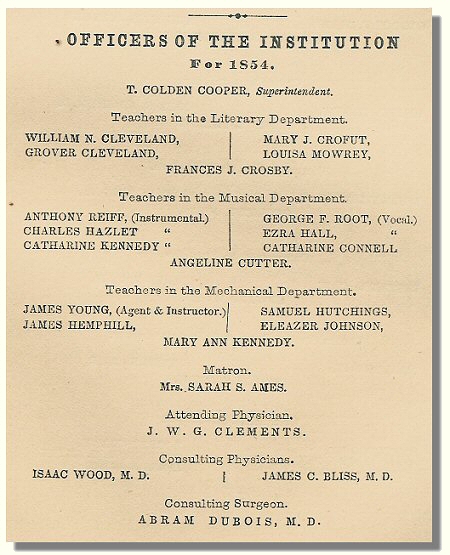

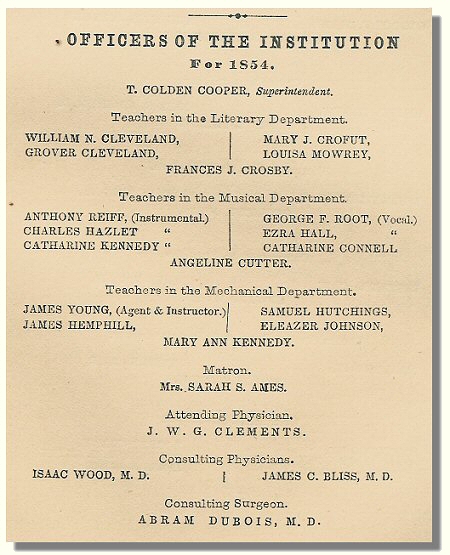

In the 1850’s one of the head teachers was William N. Cleveland, who for two years was connected with the school. His interest was temporary, as he was a student at a theological seminary near the Institution and was preparing for the ministry. His younger brother was through his influence employed first in a clerical capacity and later as both secretary and teacher in the literary department. This was Grover Cleveland.

In the 1850’s one of the head teachers was William N. Cleveland, who for two years was connected with the school. His interest was temporary, as he was a student at a theological seminary near the Institution and was preparing for the ministry. His younger brother was through his influence employed first in a clerical capacity and later as both secretary and teacher in the literary department. This was Grover Cleveland.

He is often mentioned in the autobiographies of Fanny Crosby as someone that helped her develop with her writing and helping her to be more assertive in advocating for her rights.

The youth who became President of the United States developed in the period of his service, though less than two years, an interest in the welfare of persons with blindness that he never lost.

In the 1850’s one of the head teachers was William N. Cleveland, who for two years was connected with the school. His interest was temporary, as he was a student at a theological seminary near the Institution and was preparing for the ministry. His younger brother was through his influence employed first in a clerical capacity and later as both secretary and teacher in the literary department. This was Grover Cleveland.

In the 1850’s one of the head teachers was William N. Cleveland, who for two years was connected with the school. His interest was temporary, as he was a student at a theological seminary near the Institution and was preparing for the ministry. His younger brother was through his influence employed first in a clerical capacity and later as both secretary and teacher in the literary department. This was Grover Cleveland. He is often mentioned in the autobiographies of Fanny Crosby as someone that helped her develop with her writing and helping her to be more assertive in advocating for her rights.

The youth who became President of the United States developed in the period of his service, though less than two years, an interest in the welfare of persons with blindness that he never lost.

Fanny Crosby in her book "Life Story", has this to say about Mr. Cleveland"

In 1853, our head teacher, Prof. William Cleveland, was called to New Jersey by the death of his father, a Presbyterian clergyman. After a few days absence, he returned, bringing with him his brother, a youth of 16; and the next morning afterward he came to consult me in regard to “the boy”.

“Grover has taken our father’s death very much to heart,” he said, “and I wish you would go into the office, where I have installed him as clerk, and talk to him, once in a while.”

So I went down as requested, and was introduced to the young man—not dreaming of course, that I was conversing with one destined to be twice elected to he chief magistracy of our nation.

We talked together unreservedly about his father’s death, and a bond of friendship sprung up between us, which was strengthened by subsequent interviews. He seemed a very gentile, but intensely ambitious boy, and I felt that there were great things in store for him-although, as above intimated, there was no thought in my mind that he would ever be chosen from among the millions of his country, to be hits President.

We talked together unreservedly about his father’s death, and a bond of friendship sprung up between us, which was strengthened by subsequent interviews. He seemed a very gentile, but intensely ambitious boy, and I felt that there were great things in store for him-although, as above intimated, there was no thought in my mind that he would ever be chosen from among the millions of his country, to be hits President.

Whether the death of his father had settled his mind into a serious view, or whether it was because industry and perseverance were natural to him I do not know but think each of these influences bore a part toward directing his actions.

He very seldom went out to a party or entertainment with others of the same age; but remained in his room, working away at his books. I am told that during his entire career, this faculty of hard and almost incessant work has been one of his most valuable aids.

Among other very pleasant characteristics which I noticed in him, was a disposition to help others, whenever possible. Knowing that it was great favor to me to have my poems copied neatly and legibly, he offered to perform that service to me; and I several times availed myself of his aid.

One day, just as he had finished transcribing from my memory a poem somewhat longer than usual, the man who was superintendent at that time came suddenly into the office. This was not the same gentleman who had greeted me so kindly upon my arrival, and given me such good advice; but a successor who, although wishing no doubt to do his duty, was unable at times to control his temper.

Seeing at a glance what young Mr. Grover Cleveland had been doing for me, he remonstrated, violently, gave me to understand that the clerks in the office had other work to do than copy my poetry; and hurried out of the room.

The whole affair occurred in such a whirlwind of bad humor, that I was dumbfounded, and did not know what to say or how to act. I was conscious of having done no harm in allowing the young man to write down my poetry for me, and knew not whether to rave or to adopt the good old feminine remedy of indulging in a few straightforward tears.

To my surprise, young Cleveland broke into a low but very decided laugh. “We are entirely within our rights, Fanny,” he explained, “and he had no business to interrupt or reproach us. Tomorrow, at this time, come down here with another poem; I will copy it for you; he will step into the office again, as he generally does at this time; he will no doubt ‘start in’ to administer to you another ‘going over’; and then, if I were you, I would give him a few paragraphs of plain prose, that he would not very soon forget.”

The whole event turned as Grover had foretold. The superintendent came in, just as the young man was finishing up another poem; and commenced a second series of reproaches

But I had my “prose” all ready: and imparted it to the gentleman at once. I reminded him , in as mild a voice as I could, but as firm a one as was necessary, under the circumstances, that I was a teacher there, and had rights as well as he’ that my poems had been used largely for the benefit of the Institution and that the reciting of them had not been without its mission in calling new students to us; that under such circumstances, I should claim the help of the attaches of the school, whenever they were willing to give it, without neglecting other duties; and that if he ever referred to the subject again, I should as the trustees what they thought about it.

“You will never have any more trouble with him”, laughed young Mr. Cleveland, the next time we met.

This prediction proved true; the same sagacity that has since been used in the manipulation of cabinets and councils, had almost in its very beginnings, come to the aid of a poor blind teacher.

I have since had the privilege of a very pleasant acquaintance with my boy-amanuensis: I have traced him through the different offices in which he has been entrusted with the public interests of his fellow-countrymen; have been at his home, been greeted by his sweet and accomplished wife, and held his children in my arms; and have always found him, in spirit, the same modest, sensible boy, that copied my poems years ago.

“Grover has taken our father’s death very much to heart,” he said, “and I wish you would go into the office, where I have installed him as clerk, and talk to him, once in a while.”

So I went down as requested, and was introduced to the young man—not dreaming of course, that I was conversing with one destined to be twice elected to he chief magistracy of our nation.

We talked together unreservedly about his father’s death, and a bond of friendship sprung up between us, which was strengthened by subsequent interviews. He seemed a very gentile, but intensely ambitious boy, and I felt that there were great things in store for him-although, as above intimated, there was no thought in my mind that he would ever be chosen from among the millions of his country, to be hits President.

We talked together unreservedly about his father’s death, and a bond of friendship sprung up between us, which was strengthened by subsequent interviews. He seemed a very gentile, but intensely ambitious boy, and I felt that there were great things in store for him-although, as above intimated, there was no thought in my mind that he would ever be chosen from among the millions of his country, to be hits President.Whether the death of his father had settled his mind into a serious view, or whether it was because industry and perseverance were natural to him I do not know but think each of these influences bore a part toward directing his actions.

He very seldom went out to a party or entertainment with others of the same age; but remained in his room, working away at his books. I am told that during his entire career, this faculty of hard and almost incessant work has been one of his most valuable aids.

Among other very pleasant characteristics which I noticed in him, was a disposition to help others, whenever possible. Knowing that it was great favor to me to have my poems copied neatly and legibly, he offered to perform that service to me; and I several times availed myself of his aid.

One day, just as he had finished transcribing from my memory a poem somewhat longer than usual, the man who was superintendent at that time came suddenly into the office. This was not the same gentleman who had greeted me so kindly upon my arrival, and given me such good advice; but a successor who, although wishing no doubt to do his duty, was unable at times to control his temper.

Seeing at a glance what young Mr. Grover Cleveland had been doing for me, he remonstrated, violently, gave me to understand that the clerks in the office had other work to do than copy my poetry; and hurried out of the room.

The whole affair occurred in such a whirlwind of bad humor, that I was dumbfounded, and did not know what to say or how to act. I was conscious of having done no harm in allowing the young man to write down my poetry for me, and knew not whether to rave or to adopt the good old feminine remedy of indulging in a few straightforward tears.

To my surprise, young Cleveland broke into a low but very decided laugh. “We are entirely within our rights, Fanny,” he explained, “and he had no business to interrupt or reproach us. Tomorrow, at this time, come down here with another poem; I will copy it for you; he will step into the office again, as he generally does at this time; he will no doubt ‘start in’ to administer to you another ‘going over’; and then, if I were you, I would give him a few paragraphs of plain prose, that he would not very soon forget.”

The whole event turned as Grover had foretold. The superintendent came in, just as the young man was finishing up another poem; and commenced a second series of reproaches

But I had my “prose” all ready: and imparted it to the gentleman at once. I reminded him , in as mild a voice as I could, but as firm a one as was necessary, under the circumstances, that I was a teacher there, and had rights as well as he’ that my poems had been used largely for the benefit of the Institution and that the reciting of them had not been without its mission in calling new students to us; that under such circumstances, I should claim the help of the attaches of the school, whenever they were willing to give it, without neglecting other duties; and that if he ever referred to the subject again, I should as the trustees what they thought about it.

“You will never have any more trouble with him”, laughed young Mr. Cleveland, the next time we met.

This prediction proved true; the same sagacity that has since been used in the manipulation of cabinets and councils, had almost in its very beginnings, come to the aid of a poor blind teacher.

I have since had the privilege of a very pleasant acquaintance with my boy-amanuensis: I have traced him through the different offices in which he has been entrusted with the public interests of his fellow-countrymen; have been at his home, been greeted by his sweet and accomplished wife, and held his children in my arms; and have always found him, in spirit, the same modest, sensible boy, that copied my poems years ago.

Quoted from; Crosby, Fanny. Fanny Crosby's Life Story. New York: Every Where Publishing Co., 1903. page 137-141.

On the Net

- White House Bio

- Grover Cleveland's Obituary

- "Grover the Good" - Grover Cleveland’s Birthday

- Hawaii The Overthrow of the Monarchy

- Cleveland's Congressional Address on Hawaii

- The Pullman Strike From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- White House Wedding Frances Folsom Cleveland:

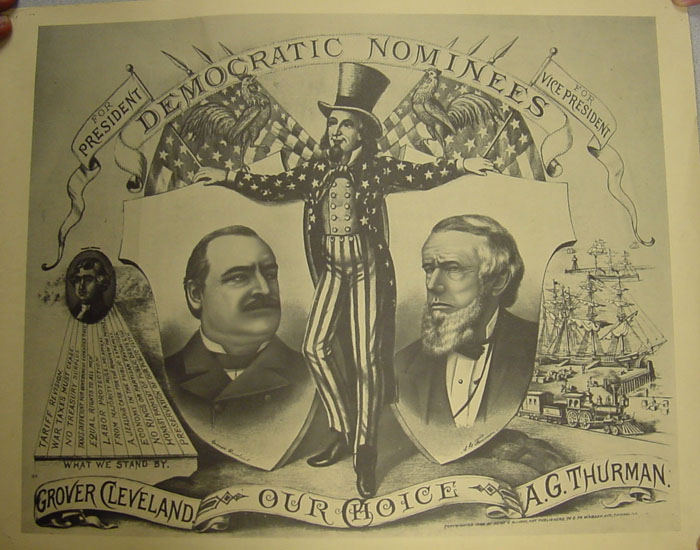

Flier from Grover Cleveland and A.G. Thurman, unsuccessful presidential and

vice presidential campaign of 1888 for the Democratic Party.

from Hudson Library & Historical Society

vice presidential campaign of 1888 for the Democratic Party.

from Hudson Library & Historical Society