Our First 100 Years

Historical Document: A Saga of Our Century (1932)

The New York Institute for Special Education 1831 Lux OriturThe following pages were transcribed from the Yearbook of The New York Institute for the Education of the Blind: One-Hundredth Year(1932, pages 41-70).

A SAGA OF OUR CENTURY

In what spirit and with what purpose a hundred years ago a group of generous souls began a movement for making the way of the blind full of the light of knowledge we are to judge by what few records are left of their words and acts. That the spirit was truly philanthropic is evidenced by the nature of the men who were responsible for providing a means whereby the blind might develop their mental powers, for they who led the movement were men known in the community for unselfish service. In such pronouncements of their enterprise as are available the profession of their dependence for guidance and for success on divine favor gives color to the statement that this movement began and continued, in the thought of many of its sponsors, as a charity. They were moved by generous sympathy for a small group whose condition excited pity. To meliorate the condition of the blind has been the actuating motive of the kindly disposed in all times.

In what spirit and with what purpose a hundred years ago a group of generous souls began a movement for making the way of the blind full of the light of knowledge we are to judge by what few records are left of their words and acts. That the spirit was truly philanthropic is evidenced by the nature of the men who were responsible for providing a means whereby the blind might develop their mental powers, for they who led the movement were men known in the community for unselfish service. In such pronouncements of their enterprise as are available the profession of their dependence for guidance and for success on divine favor gives color to the statement that this movement began and continued, in the thought of many of its sponsors, as a charity. They were moved by generous sympathy for a small group whose condition excited pity. To meliorate the condition of the blind has been the actuating motive of the kindly disposed in all times.

But the purpose was not only thus to brighten lives and lighten the burden of what appeared a heavy existence, there was also the intelligent effort to find means for schooling of the young blind. It is no wonder that this latter purpose appeared the prime object in the movement when it is remembered that of the three who are properly designated founders of The New York Institution for the Blind one was a man who had for ten years been head of a school for the deaf, another was a publisher of school books. That the third, a physician by profession, proved to be a successful teacher when he turned his powers into educational channels is the good fortune of the institution. Thus the set of the movement was determined: by personnel as well as by announced purpose its prime intent was educational. That it must depend for existence on contributions of the generous did not constitute it an eleemosynary institution, for it was not founded to bring relief to the poor, but to give light to the blind.

How this distinction has been tenaciously held and how, through the dogged perseverance of one of the school's leaders, contesting even in the courts to prove his case, and by the gradual enlightenment of the general public it is now accepted as natural and desirable will appear in the course of this narrative of the rise and growth of this the first institution, the first school on the continent of America to open its doors for the training of blind children.

THE PHILANTHROPIC URGE

The third decade of the nineteenth century seems to have been here a time for release of generous impulses. America had been an entity for a full generation and, more, had asserted her personality successfully in a war with England, and had settled to the task of finding herself in the scheme of things. And she was prospering. What more natural than that she should look for some channels in which to exhibit her power to assist others as well as to grow herself! On the seaboard cultural elements in the community life had freer course than in the less settled portions of the country. Those who had means, the financially successful merchants and professional men, remained in the east while many whose fortunes were yet to be made set out for the west, a process which has kept repeating itself as long as there remained a frontier in these United States. Philanthropic causes began to interest this public of the more fixed civilization of the east. An example that concerns quite closely our present interest was the outpoured generosity of sympathizers with the struggling Greeks. To the relief of these starving people, fighting for their liberation from Turkish oppression, shipload after shipload of food and medicines was sent. It happened that two men who became distinguished in the work of education of the blind were agents of this service to humanity: Russ of New York, Howe of Boston. Young men both and full of the ardor of generous altruism, they typified the growing interest of the new social life developing in America that began looking beyond itself.

In education this interest manifested itself in the beginnings of concern for the underprivileged. In 1807 the first school for the deaf was started. Schools for children whose parents had not the means to provide tuition in those privately operated, and until the second decade of the 19th century practically all schooling was under the control of church organizations, became the object of that philanthropic group forming the Public Free School Society. Far from the thought of those New Yorkers was the idea of the present public school system: these schools of their fostering were for the poor. All up and down the Hudson were schools conducted under church auspices and to these were sent the favored children of the people of refinement and the culture that comes through wealth. In 1826 the Public School Society became a dominant force in education and continued so until in 1853 the State took its belated step toward complete control of general educational training.

But schooling for blind children did not come within the purview of this Society. Like groups social and political of other lands and other parts of America the education of the handicapped was put in the background or became the concern of those having developed in some special way sympathy for their condition.

SAMUEL WOOD

To the intelligent activity of Samuel Akerly and the warm hearted sympathies of Samuel Wood the founding of this school was due. It is probably true that the idea of establishing for blind children an institution where they might be taught and their lives might be formed under more favorable circumstances than usually fell to their lot in the days of the early nineteenth century was formed first in the mind of Samuel Wood. He had seen in the City Almshouse children whose sight had been lost and who were eager to learn and to be occupied. Perhaps he had heard rumors or had had direct information of some movement in the interest of training the blind in Boston. Samuel Wood at this time, 1827 or '28, was in the late sixties, a prominent man of business whose small bookstore, opened in 1804, had developed into a publishing house as well as a concern dealing in books and stationery, both retail and wholesale. Always of a philanthropic turn, he had reached the age when he might leave to his sons the chief labors of their business and he could give himself more fully to matters of public and private charity. He had been a school teacher until forty years of age, hence the plight of uneducated or poorly trained children naturally claimed his interest. It is told of him that in the early years of his business career, finding that reading books for children were few in numbers and these poor in quality, he prepared and printed a primer, "The Young Child's A B C, or First Book," (1806). Such was the beginning of the publishing house, and many of its publications were children's books and school books, some of them prepared by Samuel Wood himself. It is said that he used to fill his pockets with his books and give them to children whom he met.

SAMUEL AKERLY

How this friend of childhood and of the underprivileged came to know and associate himself with Dr. Samuel Akerly in the project to establish a school for the sightless is not disclosed by any of the records. Akerly was at once superintendent, secretary and attending physician of the New York Institution for the Deaf, a scholar and an author. He had attained reputation as a physician, being associated with his brother-in-law, Samuel Latham Mitchill, one of the most eminent men in the profession of medicine in New York, had studied local geology and published a treatise on the subject, had become an enthusiast in zoology and botany. In 1821 he had been called to manage the new institution and carry on the work for the deaf which had in rather unsuccessful fashion been conducted as a private venture and without proper support since its establishment in 1807. Of this institution, now over eleven years in its second century, he was the first executive and he conducted it efficiently for more than a decade. Always active and enthusiastic, Dr. Akerly took the lead in bringing to a head the suggestions of Samuel Wood and, having interested a group of citizens of New York City in the project, prepared a bill for the incorporation of The New York Institution for the Blind and a petition to the Legislature for its enactment into law, the latter being signed by seventeen citizens; at the head of the list was the name of Samuel Wood. Prompt action was taken and incorporation was effected April 21, 1831, less than one month from the presentation of the petition. Akerly knew the ways of promoting legislation; his was the hand that guided the project through the committees and the houses of the Legislature to enactment. It is to be noted, however, that the bill as proposed by Akerly, Wood, et al., was amended and in a most vital particular. The petitioners named as the purpose of the proposed institution "to improve the moral and intellectual condition of the Blind, and to instruct them in such mechanical employments as are best adapted to persons in such a condition." The Act of Incorporation included in the first section the addition of the following words: "for the purpose of instructing children who have been born blind or who may have become blind by sickness or accident." And Akerly, who had been made president, reported at the first meeting of the Board of Managers held December 14, 1831, "The origin of this last amendment is not satisfactorily ascertained. It confines the operation of the Institution to teaching children only, and is contrary to the intentions expressed in the memorial. This provision may necessarily be the subject of a future application for an alteration." How wise was the then unknown amender, whether with intent or by accident he set the mold of the institution as a school, later developments proved, as we shall see; for it was the attempt to serve the adult blind which almost wrecked the organization(Dr. Akerly later announced that Senator Stephen Alben was responsible for the amendment).

How this friend of childhood and of the underprivileged came to know and associate himself with Dr. Samuel Akerly in the project to establish a school for the sightless is not disclosed by any of the records. Akerly was at once superintendent, secretary and attending physician of the New York Institution for the Deaf, a scholar and an author. He had attained reputation as a physician, being associated with his brother-in-law, Samuel Latham Mitchill, one of the most eminent men in the profession of medicine in New York, had studied local geology and published a treatise on the subject, had become an enthusiast in zoology and botany. In 1821 he had been called to manage the new institution and carry on the work for the deaf which had in rather unsuccessful fashion been conducted as a private venture and without proper support since its establishment in 1807. Of this institution, now over eleven years in its second century, he was the first executive and he conducted it efficiently for more than a decade. Always active and enthusiastic, Dr. Akerly took the lead in bringing to a head the suggestions of Samuel Wood and, having interested a group of citizens of New York City in the project, prepared a bill for the incorporation of The New York Institution for the Blind and a petition to the Legislature for its enactment into law, the latter being signed by seventeen citizens; at the head of the list was the name of Samuel Wood. Prompt action was taken and incorporation was effected April 21, 1831, less than one month from the presentation of the petition. Akerly knew the ways of promoting legislation; his was the hand that guided the project through the committees and the houses of the Legislature to enactment. It is to be noted, however, that the bill as proposed by Akerly, Wood, et al., was amended and in a most vital particular. The petitioners named as the purpose of the proposed institution "to improve the moral and intellectual condition of the Blind, and to instruct them in such mechanical employments as are best adapted to persons in such a condition." The Act of Incorporation included in the first section the addition of the following words: "for the purpose of instructing children who have been born blind or who may have become blind by sickness or accident." And Akerly, who had been made president, reported at the first meeting of the Board of Managers held December 14, 1831, "The origin of this last amendment is not satisfactorily ascertained. It confines the operation of the Institution to teaching children only, and is contrary to the intentions expressed in the memorial. This provision may necessarily be the subject of a future application for an alteration." How wise was the then unknown amender, whether with intent or by accident he set the mold of the institution as a school, later developments proved, as we shall see; for it was the attempt to serve the adult blind which almost wrecked the organization(Dr. Akerly later announced that Senator Stephen Alben was responsible for the amendment).

JOHN DENNISON RUSS

President Akerly reported at this first meeting of the Managers, at which eight of the twenty designated as the Board were present, that "during the past summer, in company with Dr. Russ, he had visited the Almshouse to see the Blind in that Institution." Thus enters officially into the picture the man who was to become first teacher of the first class of blind children to receive formal instruction in the United States. The story goes that Dr. John D. Russ, who had but recently returned from philanthropic service in Greece and who had proposed on his own account to provide instruction of the blind children in the City Almshouse, was introduced to Dr. Akerly and was made acquainted with the incorporation of an institution with this purpose. Thereupon they agreed to work out together the problem. At the second meeting of the Board of Managers Dr. Russ was elected a member thereof, taking the place of one manager who had refused to serve.

Russ had agreed with Akerly that he would himself teach such children as might be organized into a class for instruction, serving gratuitously; accordingly, on March 15, 1832, permission having been given the Board of Managers by the city authorities, three boys were brought from the Almshouse to the home of a widow on Canal Street, who engaged to care for them, and Dr. Russ began to teach them. About two months later three more boys were added and the school was moved to 47 Mercer Street. It was all experiment. The teacher was a novice, the methods and apparatus especially adapted to instructing the blind had to be discovered or procured; there had come to these pioneers only a little aid through a communication from James Gall, Principal of the Edinburgh school. And there was no substantial amount of money for expenses. But success attended the effort from the start. One can readily believe that the boys who constituted the school were eager to learn and grateful to be removed from the depressing atmosphere of the Almshouse. Some were bright boys, as their later life evidenced. One displayed literary talent of good degree, another became a minister of the gospel and was later superintendent of two southern schools for the blind. Pride in achievement of the five boys of the new school (one had died of cholera in August, 1832 was one reason for arranging a public examination after some nine months of effort, but it may readily be believed that the insistent need for funds had more to do with the making of a demonstration that would arouse the interest and stimulate the generosity of such philanthropic citizens as might be induced to attend. The examination was held at the City Hotel, December 13, and was a pronounced success both as a proof of the worthiness of the effort to instruct the blind and as a means of raising funds.

EFFORTS TOWARD SECURITY

About the beginnings of most ventures clings an atmosphere of romance. Else at this moment, a century after the events here now recorded, we should not be occupied in recreating t he scene and living over in imagination the experiences of those who began to render a service to the blind long since justified in the public view. Into the gratification of the teacher who saw his pupils give evidence of their good training we can enter, with the thrill of satisfaction that men and women of intelligence and generous impulses were giving approval to their enterprise which the Managers experienced as some hundreds of dollars were contributed with promise of continued support we, too, can be stimulated. Referring to this successful public venture of the infant institution to prove its right to exist, the President of the Board of Managers wrote: "From this period a deeper interest was felt in the prosperity of the Institution, and the year 1833 commenced with brighter prospects. By the persevering and indefatigable exertions of Samuel Wood and some others [Dr. Akerly is most modest!], $579 were raised by subscription and all the expenses incurred to 1st January, 1833, were liquidated and paid. From this time we may date the certain existence of the Institution."

he scene and living over in imagination the experiences of those who began to render a service to the blind long since justified in the public view. Into the gratification of the teacher who saw his pupils give evidence of their good training we can enter, with the thrill of satisfaction that men and women of intelligence and generous impulses were giving approval to their enterprise which the Managers experienced as some hundreds of dollars were contributed with promise of continued support we, too, can be stimulated. Referring to this successful public venture of the infant institution to prove its right to exist, the President of the Board of Managers wrote: "From this period a deeper interest was felt in the prosperity of the Institution, and the year 1833 commenced with brighter prospects. By the persevering and indefatigable exertions of Samuel Wood and some others [Dr. Akerly is most modest!], $579 were raised by subscription and all the expenses incurred to 1st January, 1833, were liquidated and paid. From this time we may date the certain existence of the Institution."

But it was, indeed, an uphill battle those Managers fought.

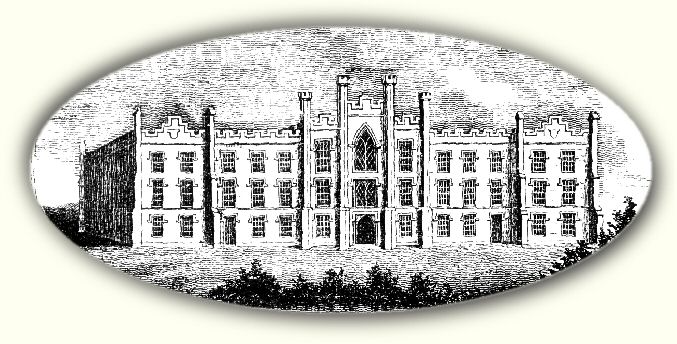

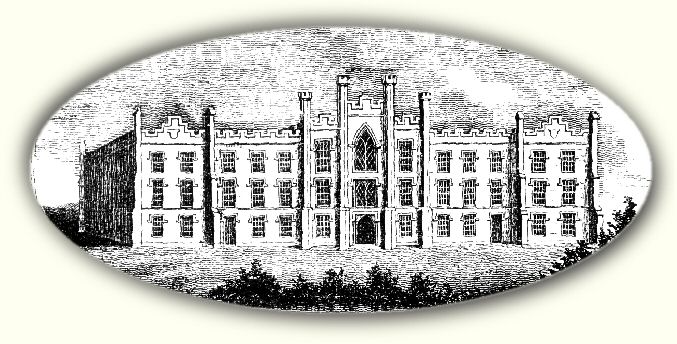

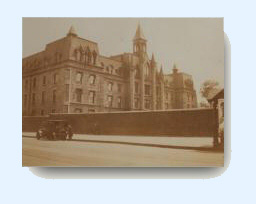

Indifference of the public and incredulity as to the possibility of teaching the blind persisted. To secure funds for continuance of the institution was the greatest and the constant anxiety of the faithful ones. And these who were deeply enough interested to give their time and energies in support of the three founders, Wood, Akerly and Russ, numbered a scant half dozen of the Managers. It is interesting to note also that Dr. Akerly drafted members of his family to become Managers, two his brothers-in-law, one the husband of his own daughter. And to one of these relatives, Morris Ketchum, husband of Dr. Akerly's sister, fell the honor of attracting the interest of James Boorman, the first benefactor in a long line of generous givers. Mr. Ketchum, it is reported, set out early in 1833 with a blank book to solicit signatures therein for subscriptions, seeking one hundred dollar contributors. When he called on Mr. Boorman, a leading merchant of that day, he was met with an offer to do something better than subscribe the modest sum requested. On Ninth Avenue at 34th Street Mr. Boorman stated that he owned a plot of ground on which was a large unoccupied house and this property he proposed to rent to the Managers for a nominal sum with the privilege of purchase if found suitable. In a few years the property was bought from Mr. Boorman at a price far below its real value and thus was the Institution provided with a site and thereon was built, beginning in 1837, the substantial stone structure which for 87 years housed the school and was a famous landmark in that section of the city.

THE EARLY YEARS

Dr. Russ proved to be a teacher of skill and resourcefulness. His instructions ranged the whole field of the usual subjects of schooling in letters and at first he trained his young charges in hand work as well. The tools of his teaching and the methods he used were for the most part his own invention. What teaching assistance he had is not revealed by the records save in the book of minutes of the Managers we learn that a lady teacher of singing was employed and a blind teacher of hand work was secured from Edinburgh, both in 1833. After being located in Mercer Street for nearly a year a removal to 62 Spring Street was made. Ten pupils, four of them girls, had joined the six beginners. It was a notable event when on October 10, 1833, the large house on the Boorman plot which had been put in order for them received the pupils and others of the household. Dr. Russ had done his work as a teacher and practiced his profession as a doctor of medicine during the time the school was in town, but the removal to so remote a place as the Ninth Avenue at 34th Street obliged him to abandon to a great extent his practice. Up to this time he had served gratuitously. He was now put on salary and was required to live at the Institution.

The fame of the school was enhanced by the successful visit of the Superintendent "to the north and west" (in New York State) in the summer of 1833 with six of his pupils, undertaken to show the public what was possible in the matter of teaching the blind. Probably as the direct result of such advertising, the first provision for admission of pupils at expense of the State of New York was made by legislative enactment in May, 1834. Thereafter the State has continued its patronage in some sort year by year. The enrollment increased, the number of pupils being 26 at the end of 1834; ten of these were State pupils. New Jersey has also patronized the Institute by sending many of its sightless children here for training. The Superintendent now had as helpers for instructional purposes one teacher of literary subjects, a foreman of mechanical pursuits, and a teacher of music. In November, 1834, some disagreement arose between the Managers and Dr. Russ, the latter desiring to live elsewhere than in the Institution and devote only a portion of his time to the school. This proposal was not satisfactory to some of the Managers. Negotiations were carried on for some time in the effort to secure an agreement; these proved futile and with the acceptance of his resignation Dr. Russ's connection with the Institution was severed in February, 1835.

In the brief period of his service Dr. Russ achieved results most remarkable. Besides carrying on instruction of his pupils and conducting the business of the Institution, he invented apparatus for the use of the blind, essayed to discover a means of reducing the size of books for the sightless, proposing a phonetic alphabet with forty characters and representation thereof by dots and lines, adapted and improved the methods used in European schools for representing geographical information. His chief concern seems to have been to open the way and provide the means for the intellectual development of the blind and to this end he gave his enthusiastic and untiring efforts. Into other philanthropic channels his talents were directed through more than two decades after leaving the Institution. In 1858 he retired from active work, and it is interesting to note that his desire to serve the blind inspired him to spend many years of his leisure in studies such as he had begun while the Superintendent of the Institution.

LABORS OF THE MANAGERS

Whoever follows with curious interest or as a student the history of this organization during the course of three decades from its beginning to the 60's will be struck with the remarkable fidelity of certain of the Managers to the task of conducting the Institution. Chief of these was Dr. Akerly; after him Dr. Isaac Wood, son of Samuel Wood; George F. Allen and Silas Brown, to cite only a few whose long and devoted service deserves more than the brief mention here accorded. Five of the Wood family have been Managers: Samuel Wood, Dr. Isaac Wood, John Wood, Edward Wood and Arnold Wood; the last named great-grandson of the founder being a present member of the Board.

One whose name must always be gratefully remembered for long and intelligent participation in the work of the Institution is Anson G. Phelps, elected a Manager December 30, 1833, made Vice President 1837 and chosen President in succession to Dr. Akerly 1842, serving from 1843 to 1853- A man of great influence in the community, successful in business, a philanthropist, a man of marked piety.

Acceptance of the responsibility of a manager in those days meant actual attention to the details of administration. The minutes of the Board of Managers reveal that the meetings were concerned with every sort of matter: the employment of superintendent and all the intermediates to assistant gardener, the adjudication of matters of discipline and the reprimanding or dismissal of children who were naughty, the procuring of utensils and of food; for example, here is one quotation;:

"The President reports' that a contract had been made with a Baker to bake flour furnished by the institution from twelve shillings per barrel and furnish 280 pounds of bread from each barrel."

The insistent demands of any going concerti for the necessary funds also occupied the time and demanded the personal effort of each Manager. It is not surprising to find that many of those chosen Managers served but a short time, a year or two, and that of the first seventy-five who accepted the office only thirteen endured ten years or more. It was an onerous task and one to be carried on only by truly interested and enthusiastic men.

It was necessary, doubtless, that the detailed management should be thus provided, for the office of Superintendent was filled by a succession of short term incumbents only one of whom continued as long as nine years. After Russ, in twenty years six persons held each for a short period the superintendency. What impress of personality or educational leadership may have been left by these men, save perhaps one, is not revealed in any available records; it is quite impossible that any one, other than such a genius as was Russ, could in two or three years make any impressive contribution. And until the year 1852 no superintendent had had the opportunity to disclose in a published annual report the theory or the practice of his professional sponsorship.

OFFICIAL ACCOUNTING OF STEWARDSHIP

In fact, no reports were published by the Institution until 1837 when the First Annual Report of the Managers was made to the Legislature in obedience to requirement of law, the new organization having been given State aid in the preceding year. This First Report disclosed the steps by which from 1831 through travail of inadequate financial resources and slowly growing public interest the infant Institution had in five years become established and was able to balance its budget. Each of the succeeding Reports, growing steadily in interest to the general reader as the school grew, and the themes were not always the money subject, reflected the devotion of the Managers; presumably the First to the Fourth inclusive are from the hand of Dr. Samuel Akerly. The literary style of the later Reports, as well as their substance, reveals another mind; whose knowledge of the working of the establishment and whose spirit are thus disclosed may be best inferred from the perusal of the Tenth Report, which is signed "Anson G. Phelps, President." Thus it is likely that the voice of the Board of Managers was through all this inchoate period of finding the way, of changing leadership in the school itself, the capable, devoted, responsible President. With the Seventeenth Report,that for 1852, Mr. Phelps made his last contribution to our literature, for in November, 1853, his death occurred.

With the Superintendent's Report prepared by T. Colden Cooper for 1852 the student of the history of the New York Institution finds a beginning of a long series of statements revealing the purposes and ideals of the school as evolved in the mind of the educational leader and his record of its achievements. To this writer it appears obvious that with the six years during which James F. Chamberlain was Superintendent a sense of the importance of having a continuing school policy, directed by the Board's agent, had grown in the minds of the Managers. Mr. Cooper was the first exemplar of this development and he was able to carry out his plans through nine years. His successor, Mr. Robert G. Rankin, occupied the post of Superintendent two years and was followed by William Bell Wait.

SOME PERSONS AND PRACTICES OF THE '40's AND '50's

Concerning James F. Chamberlain, teacher and Superintendent, it should be said that his influence through the years from 1842 to 1852 was probably the chief cohesive element in the school's life. It was a benign influence, as we learn from the testimony of his successor and from a distinguished pupil and teacher, Fanny Crosby. It is to be regretted that there are not available any writings of his authorship by which to measure him.

Through the reports of Mr. Cooper one is given an exposition of the methods of teaching in the classes, the program of studies, the basis in educational theory on which the work proceeded at this stage of progress, the third decade. The writer of these reports reveals himself, particularly in the Seventeenth to the Twenty second inclusive, as an educator of ability to explore and describe the whole problem. There is a spirit of optimism in his pronouncements, though in the discussion of some difficulties he looks them squarely in the face. In particular, there is the problem of the manufactory which the Board for years in its great desire to benefit the adult blind had fostered. This problem had become so acute through the financial losses that disaster to the whole organization threatened. The Superintendent as an educator rightly viewed this as an excrescence which should be removed. (And later it was removed.) It was early in Mr. Cooper's superintendency that the first convention of instructors of the blind was held and the New York Institution was host.

One of the head teachers of this period was William N. Cleveland, who for two years was connected with the school. His interest was temporary, as he was a student of the Theological Seminary, neighbor to the Institution, preparing for the ministry. His younger brother was through his influence employed first in a clerical capacity and later as both secretary and teacher in the literary department. This was Grover Cleveland. The youth who became President of the United States developed in the period of his service, though less than two years, an interest in the welfare of the sightless that he never lost.

In carrying on the task of instruction there seems to have been not only faithful service by teachers of ability but more, a comradeship of mutual assistance in developing a body of methods specially adapted to teaching the blind. That some were actuated by deep religious fervor in this work is undoubtedly true. In selection of teachers the Managers were frequently assured by the committees offering candidates that they were "of excellent Christian character." It was natural that a philanthropy conceived in a community dominated by people of three strong Protestant churches should have a care for religion. And some of the pupils became devoutly engaged in things spiritual.' The most notable instance of this is the case of Frances Jane Crosby, teacher for many years in the Institution, writer of hymns of wide acceptance and use in the 19th century. Contributing to this phase of the influences under which the pupils of the early decades lived was the employment of George F. Root for years as teacher of vocal music, he who became a noted writer of church music. And a contributor to continuity of instruction and holding of the school to excellence of accomplishment was Anthony J. Reiff, music master for twenty-eight years.

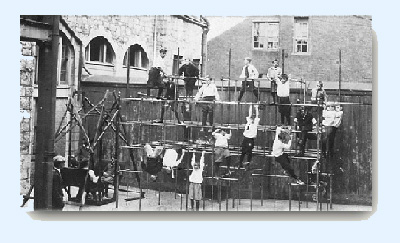

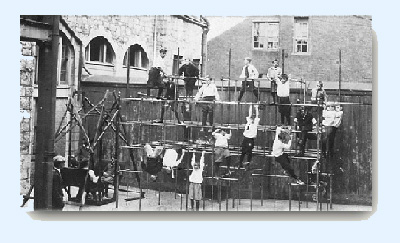

From its beginning the New York Institution was committed to the policy of providing manual instruction for its pupils, so much so that in one of the reports of Superintendent Cooper (1853) occurs the comment: "The schools are thus somewhat on the manual labor plan." Skill in manual arts and the manufacture of articles for sale was encouraged and over and over again the authorities of the school petitioned the Legislature for additional support that adult blind people might be employed under the auspices of the Institution. How this was tried and found impracticable is a part of the history that fashioned the later insistence on much training of the hands for physical and cultural effect rather than for industrial purposes.

MEN OF MARK AS MANAGERS

In attempting to complete the picture of the conditions as they were at the beginning of the Wait regime it is quite important for the narrator to introduce some personalities that were to affect the history of the Institution mightily. The President of the Board of Managers with whom he was to begin his association was Augustus Schell, and as President he was to continue through more than twenty years; he had been a member of the Board since 1849; a man of commanding influence. Another member was Alfred Schermerhorn, whose name at once recalls the long-continued devotion of the family to the interests of the Institution. First of this name to become Manager was Peter Augustus Schermerhorn, beginning his service in 1839. A fourth was ' William C. Schermerhorn, who from 1866 to 1901 remained a most devoted friend. His nephew, F. Augustus Schermerhorn, entered on a notable career as Manager in 1870 and for forty years, ten of them as President, gave this school generously his time and interest, besides making special gifts of money for particular needs. The Institution was to him like his child, for there was nothing too much for him to do to advance its interests. At his death half his estate became through his munificence the property of the Institute. A cousin, Alfred E. Schermerhorn, carried on later the tradition and his son, seventh of the name on the roster of Managers, serves today to continue an official interest manifested by this family through most of the century since 1832.

The mention in this connection of others who made possible by loyal support the successful progress of Wait's administration would include William Whitewright, who served longest of any of the Treasurers, a quarter century, Peter Marie, John I. Kane, Frederick W. Rhinelander, Chandler Robbins. These, with others, gave long and faithful support in the years of the school's development to a commanding position in the field of education of the blind.

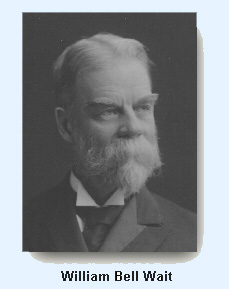

WILLIAM BELL WAIT

Graduated in June, 1859, from Albany Normal College, William Bell Wait, at 20 years of age, became that same year a teacher in the literary department of the New York Institution for the Blind. At the end of two years he left to study law and was admitted to the bar in 1862. He then became the superintendent of schools of Kingston, N. Y., but was chosen Superintendent of the New York Institution and began his service here October 1, 1863. He was but 24 years old and before him was a task that might well have daunted a man of experience and tried powers.

Graduated in June, 1859, from Albany Normal College, William Bell Wait, at 20 years of age, became that same year a teacher in the literary department of the New York Institution for the Blind. At the end of two years he left to study law and was admitted to the bar in 1862. He then became the superintendent of schools of Kingston, N. Y., but was chosen Superintendent of the New York Institution and began his service here October 1, 1863. He was but 24 years old and before him was a task that might well have daunted a man of experience and tried powers.

The New York Institute for Special Education 1831 Lux OriturThe following pages were transcribed from the Yearbook of The New York Institute for the Education of the Blind: One-Hundredth Year(1932, pages 41-70).

A SAGA OF OUR CENTURY

In what spirit and with what purpose a hundred years ago a group of generous souls began a movement for making the way of the blind full of the light of knowledge we are to judge by what few records are left of their words and acts. That the spirit was truly philanthropic is evidenced by the nature of the men who were responsible for providing a means whereby the blind might develop their mental powers, for they who led the movement were men known in the community for unselfish service. In such pronouncements of their enterprise as are available the profession of their dependence for guidance and for success on divine favor gives color to the statement that this movement began and continued, in the thought of many of its sponsors, as a charity. They were moved by generous sympathy for a small group whose condition excited pity. To meliorate the condition of the blind has been the actuating motive of the kindly disposed in all times.

In what spirit and with what purpose a hundred years ago a group of generous souls began a movement for making the way of the blind full of the light of knowledge we are to judge by what few records are left of their words and acts. That the spirit was truly philanthropic is evidenced by the nature of the men who were responsible for providing a means whereby the blind might develop their mental powers, for they who led the movement were men known in the community for unselfish service. In such pronouncements of their enterprise as are available the profession of their dependence for guidance and for success on divine favor gives color to the statement that this movement began and continued, in the thought of many of its sponsors, as a charity. They were moved by generous sympathy for a small group whose condition excited pity. To meliorate the condition of the blind has been the actuating motive of the kindly disposed in all times.But the purpose was not only thus to brighten lives and lighten the burden of what appeared a heavy existence, there was also the intelligent effort to find means for schooling of the young blind. It is no wonder that this latter purpose appeared the prime object in the movement when it is remembered that of the three who are properly designated founders of The New York Institution for the Blind one was a man who had for ten years been head of a school for the deaf, another was a publisher of school books. That the third, a physician by profession, proved to be a successful teacher when he turned his powers into educational channels is the good fortune of the institution. Thus the set of the movement was determined: by personnel as well as by announced purpose its prime intent was educational. That it must depend for existence on contributions of the generous did not constitute it an eleemosynary institution, for it was not founded to bring relief to the poor, but to give light to the blind.

How this distinction has been tenaciously held and how, through the dogged perseverance of one of the school's leaders, contesting even in the courts to prove his case, and by the gradual enlightenment of the general public it is now accepted as natural and desirable will appear in the course of this narrative of the rise and growth of this the first institution, the first school on the continent of America to open its doors for the training of blind children.

THE PHILANTHROPIC URGE

The third decade of the nineteenth century seems to have been here a time for release of generous impulses. America had been an entity for a full generation and, more, had asserted her personality successfully in a war with England, and had settled to the task of finding herself in the scheme of things. And she was prospering. What more natural than that she should look for some channels in which to exhibit her power to assist others as well as to grow herself! On the seaboard cultural elements in the community life had freer course than in the less settled portions of the country. Those who had means, the financially successful merchants and professional men, remained in the east while many whose fortunes were yet to be made set out for the west, a process which has kept repeating itself as long as there remained a frontier in these United States. Philanthropic causes began to interest this public of the more fixed civilization of the east. An example that concerns quite closely our present interest was the outpoured generosity of sympathizers with the struggling Greeks. To the relief of these starving people, fighting for their liberation from Turkish oppression, shipload after shipload of food and medicines was sent. It happened that two men who became distinguished in the work of education of the blind were agents of this service to humanity: Russ of New York, Howe of Boston. Young men both and full of the ardor of generous altruism, they typified the growing interest of the new social life developing in America that began looking beyond itself.

In education this interest manifested itself in the beginnings of concern for the underprivileged. In 1807 the first school for the deaf was started. Schools for children whose parents had not the means to provide tuition in those privately operated, and until the second decade of the 19th century practically all schooling was under the control of church organizations, became the object of that philanthropic group forming the Public Free School Society. Far from the thought of those New Yorkers was the idea of the present public school system: these schools of their fostering were for the poor. All up and down the Hudson were schools conducted under church auspices and to these were sent the favored children of the people of refinement and the culture that comes through wealth. In 1826 the Public School Society became a dominant force in education and continued so until in 1853 the State took its belated step toward complete control of general educational training.

But schooling for blind children did not come within the purview of this Society. Like groups social and political of other lands and other parts of America the education of the handicapped was put in the background or became the concern of those having developed in some special way sympathy for their condition.

SAMUEL WOOD

To the intelligent activity of Samuel Akerly and the warm hearted sympathies of Samuel Wood the founding of this school was due. It is probably true that the idea of establishing for blind children an institution where they might be taught and their lives might be formed under more favorable circumstances than usually fell to their lot in the days of the early nineteenth century was formed first in the mind of Samuel Wood. He had seen in the City Almshouse children whose sight had been lost and who were eager to learn and to be occupied. Perhaps he had heard rumors or had had direct information of some movement in the interest of training the blind in Boston. Samuel Wood at this time, 1827 or '28, was in the late sixties, a prominent man of business whose small bookstore, opened in 1804, had developed into a publishing house as well as a concern dealing in books and stationery, both retail and wholesale. Always of a philanthropic turn, he had reached the age when he might leave to his sons the chief labors of their business and he could give himself more fully to matters of public and private charity. He had been a school teacher until forty years of age, hence the plight of uneducated or poorly trained children naturally claimed his interest. It is told of him that in the early years of his business career, finding that reading books for children were few in numbers and these poor in quality, he prepared and printed a primer, "The Young Child's A B C, or First Book," (1806). Such was the beginning of the publishing house, and many of its publications were children's books and school books, some of them prepared by Samuel Wood himself. It is said that he used to fill his pockets with his books and give them to children whom he met.

SAMUEL AKERLY

How this friend of childhood and of the underprivileged came to know and associate himself with Dr. Samuel Akerly in the project to establish a school for the sightless is not disclosed by any of the records. Akerly was at once superintendent, secretary and attending physician of the New York Institution for the Deaf, a scholar and an author. He had attained reputation as a physician, being associated with his brother-in-law, Samuel Latham Mitchill, one of the most eminent men in the profession of medicine in New York, had studied local geology and published a treatise on the subject, had become an enthusiast in zoology and botany. In 1821 he had been called to manage the new institution and carry on the work for the deaf which had in rather unsuccessful fashion been conducted as a private venture and without proper support since its establishment in 1807. Of this institution, now over eleven years in its second century, he was the first executive and he conducted it efficiently for more than a decade. Always active and enthusiastic, Dr. Akerly took the lead in bringing to a head the suggestions of Samuel Wood and, having interested a group of citizens of New York City in the project, prepared a bill for the incorporation of The New York Institution for the Blind and a petition to the Legislature for its enactment into law, the latter being signed by seventeen citizens; at the head of the list was the name of Samuel Wood. Prompt action was taken and incorporation was effected April 21, 1831, less than one month from the presentation of the petition. Akerly knew the ways of promoting legislation; his was the hand that guided the project through the committees and the houses of the Legislature to enactment. It is to be noted, however, that the bill as proposed by Akerly, Wood, et al., was amended and in a most vital particular. The petitioners named as the purpose of the proposed institution "to improve the moral and intellectual condition of the Blind, and to instruct them in such mechanical employments as are best adapted to persons in such a condition." The Act of Incorporation included in the first section the addition of the following words: "for the purpose of instructing children who have been born blind or who may have become blind by sickness or accident." And Akerly, who had been made president, reported at the first meeting of the Board of Managers held December 14, 1831, "The origin of this last amendment is not satisfactorily ascertained. It confines the operation of the Institution to teaching children only, and is contrary to the intentions expressed in the memorial. This provision may necessarily be the subject of a future application for an alteration." How wise was the then unknown amender, whether with intent or by accident he set the mold of the institution as a school, later developments proved, as we shall see; for it was the attempt to serve the adult blind which almost wrecked the organization(Dr. Akerly later announced that Senator Stephen Alben was responsible for the amendment).

How this friend of childhood and of the underprivileged came to know and associate himself with Dr. Samuel Akerly in the project to establish a school for the sightless is not disclosed by any of the records. Akerly was at once superintendent, secretary and attending physician of the New York Institution for the Deaf, a scholar and an author. He had attained reputation as a physician, being associated with his brother-in-law, Samuel Latham Mitchill, one of the most eminent men in the profession of medicine in New York, had studied local geology and published a treatise on the subject, had become an enthusiast in zoology and botany. In 1821 he had been called to manage the new institution and carry on the work for the deaf which had in rather unsuccessful fashion been conducted as a private venture and without proper support since its establishment in 1807. Of this institution, now over eleven years in its second century, he was the first executive and he conducted it efficiently for more than a decade. Always active and enthusiastic, Dr. Akerly took the lead in bringing to a head the suggestions of Samuel Wood and, having interested a group of citizens of New York City in the project, prepared a bill for the incorporation of The New York Institution for the Blind and a petition to the Legislature for its enactment into law, the latter being signed by seventeen citizens; at the head of the list was the name of Samuel Wood. Prompt action was taken and incorporation was effected April 21, 1831, less than one month from the presentation of the petition. Akerly knew the ways of promoting legislation; his was the hand that guided the project through the committees and the houses of the Legislature to enactment. It is to be noted, however, that the bill as proposed by Akerly, Wood, et al., was amended and in a most vital particular. The petitioners named as the purpose of the proposed institution "to improve the moral and intellectual condition of the Blind, and to instruct them in such mechanical employments as are best adapted to persons in such a condition." The Act of Incorporation included in the first section the addition of the following words: "for the purpose of instructing children who have been born blind or who may have become blind by sickness or accident." And Akerly, who had been made president, reported at the first meeting of the Board of Managers held December 14, 1831, "The origin of this last amendment is not satisfactorily ascertained. It confines the operation of the Institution to teaching children only, and is contrary to the intentions expressed in the memorial. This provision may necessarily be the subject of a future application for an alteration." How wise was the then unknown amender, whether with intent or by accident he set the mold of the institution as a school, later developments proved, as we shall see; for it was the attempt to serve the adult blind which almost wrecked the organization(Dr. Akerly later announced that Senator Stephen Alben was responsible for the amendment).JOHN DENNISON RUSS

President Akerly reported at this first meeting of the Managers, at which eight of the twenty designated as the Board were present, that "during the past summer, in company with Dr. Russ, he had visited the Almshouse to see the Blind in that Institution." Thus enters officially into the picture the man who was to become first teacher of the first class of blind children to receive formal instruction in the United States. The story goes that Dr. John D. Russ, who had but recently returned from philanthropic service in Greece and who had proposed on his own account to provide instruction of the blind children in the City Almshouse, was introduced to Dr. Akerly and was made acquainted with the incorporation of an institution with this purpose. Thereupon they agreed to work out together the problem. At the second meeting of the Board of Managers Dr. Russ was elected a member thereof, taking the place of one manager who had refused to serve.

Russ had agreed with Akerly that he would himself teach such children as might be organized into a class for instruction, serving gratuitously; accordingly, on March 15, 1832, permission having been given the Board of Managers by the city authorities, three boys were brought from the Almshouse to the home of a widow on Canal Street, who engaged to care for them, and Dr. Russ began to teach them. About two months later three more boys were added and the school was moved to 47 Mercer Street. It was all experiment. The teacher was a novice, the methods and apparatus especially adapted to instructing the blind had to be discovered or procured; there had come to these pioneers only a little aid through a communication from James Gall, Principal of the Edinburgh school. And there was no substantial amount of money for expenses. But success attended the effort from the start. One can readily believe that the boys who constituted the school were eager to learn and grateful to be removed from the depressing atmosphere of the Almshouse. Some were bright boys, as their later life evidenced. One displayed literary talent of good degree, another became a minister of the gospel and was later superintendent of two southern schools for the blind. Pride in achievement of the five boys of the new school (one had died of cholera in August, 1832 was one reason for arranging a public examination after some nine months of effort, but it may readily be believed that the insistent need for funds had more to do with the making of a demonstration that would arouse the interest and stimulate the generosity of such philanthropic citizens as might be induced to attend. The examination was held at the City Hotel, December 13, and was a pronounced success both as a proof of the worthiness of the effort to instruct the blind and as a means of raising funds.

EFFORTS TOWARD SECURITY

About the beginnings of most ventures clings an atmosphere of romance. Else at this moment, a century after the events here now recorded, we should not be occupied in recreating t

he scene and living over in imagination the experiences of those who began to render a service to the blind long since justified in the public view. Into the gratification of the teacher who saw his pupils give evidence of their good training we can enter, with the thrill of satisfaction that men and women of intelligence and generous impulses were giving approval to their enterprise which the Managers experienced as some hundreds of dollars were contributed with promise of continued support we, too, can be stimulated. Referring to this successful public venture of the infant institution to prove its right to exist, the President of the Board of Managers wrote: "From this period a deeper interest was felt in the prosperity of the Institution, and the year 1833 commenced with brighter prospects. By the persevering and indefatigable exertions of Samuel Wood and some others [Dr. Akerly is most modest!], $579 were raised by subscription and all the expenses incurred to 1st January, 1833, were liquidated and paid. From this time we may date the certain existence of the Institution."

he scene and living over in imagination the experiences of those who began to render a service to the blind long since justified in the public view. Into the gratification of the teacher who saw his pupils give evidence of their good training we can enter, with the thrill of satisfaction that men and women of intelligence and generous impulses were giving approval to their enterprise which the Managers experienced as some hundreds of dollars were contributed with promise of continued support we, too, can be stimulated. Referring to this successful public venture of the infant institution to prove its right to exist, the President of the Board of Managers wrote: "From this period a deeper interest was felt in the prosperity of the Institution, and the year 1833 commenced with brighter prospects. By the persevering and indefatigable exertions of Samuel Wood and some others [Dr. Akerly is most modest!], $579 were raised by subscription and all the expenses incurred to 1st January, 1833, were liquidated and paid. From this time we may date the certain existence of the Institution."But it was, indeed, an uphill battle those Managers fought.

Indifference of the public and incredulity as to the possibility of teaching the blind persisted. To secure funds for continuance of the institution was the greatest and the constant anxiety of the faithful ones. And these who were deeply enough interested to give their time and energies in support of the three founders, Wood, Akerly and Russ, numbered a scant half dozen of the Managers. It is interesting to note also that Dr. Akerly drafted members of his family to become Managers, two his brothers-in-law, one the husband of his own daughter. And to one of these relatives, Morris Ketchum, husband of Dr. Akerly's sister, fell the honor of attracting the interest of James Boorman, the first benefactor in a long line of generous givers. Mr. Ketchum, it is reported, set out early in 1833 with a blank book to solicit signatures therein for subscriptions, seeking one hundred dollar contributors. When he called on Mr. Boorman, a leading merchant of that day, he was met with an offer to do something better than subscribe the modest sum requested. On Ninth Avenue at 34th Street Mr. Boorman stated that he owned a plot of ground on which was a large unoccupied house and this property he proposed to rent to the Managers for a nominal sum with the privilege of purchase if found suitable. In a few years the property was bought from Mr. Boorman at a price far below its real value and thus was the Institution provided with a site and thereon was built, beginning in 1837, the substantial stone structure which for 87 years housed the school and was a famous landmark in that section of the city.

THE EARLY YEARS

Dr. Russ proved to be a teacher of skill and resourcefulness. His instructions ranged the whole field of the usual subjects of schooling in letters and at first he trained his young charges in hand work as well. The tools of his teaching and the methods he used were for the most part his own invention. What teaching assistance he had is not revealed by the records save in the book of minutes of the Managers we learn that a lady teacher of singing was employed and a blind teacher of hand work was secured from Edinburgh, both in 1833. After being located in Mercer Street for nearly a year a removal to 62 Spring Street was made. Ten pupils, four of them girls, had joined the six beginners. It was a notable event when on October 10, 1833, the large house on the Boorman plot which had been put in order for them received the pupils and others of the household. Dr. Russ had done his work as a teacher and practiced his profession as a doctor of medicine during the time the school was in town, but the removal to so remote a place as the Ninth Avenue at 34th Street obliged him to abandon to a great extent his practice. Up to this time he had served gratuitously. He was now put on salary and was required to live at the Institution.

The fame of the school was enhanced by the successful visit of the Superintendent "to the north and west" (in New York State) in the summer of 1833 with six of his pupils, undertaken to show the public what was possible in the matter of teaching the blind. Probably as the direct result of such advertising, the first provision for admission of pupils at expense of the State of New York was made by legislative enactment in May, 1834. Thereafter the State has continued its patronage in some sort year by year. The enrollment increased, the number of pupils being 26 at the end of 1834; ten of these were State pupils. New Jersey has also patronized the Institute by sending many of its sightless children here for training. The Superintendent now had as helpers for instructional purposes one teacher of literary subjects, a foreman of mechanical pursuits, and a teacher of music. In November, 1834, some disagreement arose between the Managers and Dr. Russ, the latter desiring to live elsewhere than in the Institution and devote only a portion of his time to the school. This proposal was not satisfactory to some of the Managers. Negotiations were carried on for some time in the effort to secure an agreement; these proved futile and with the acceptance of his resignation Dr. Russ's connection with the Institution was severed in February, 1835.

In the brief period of his service Dr. Russ achieved results most remarkable. Besides carrying on instruction of his pupils and conducting the business of the Institution, he invented apparatus for the use of the blind, essayed to discover a means of reducing the size of books for the sightless, proposing a phonetic alphabet with forty characters and representation thereof by dots and lines, adapted and improved the methods used in European schools for representing geographical information. His chief concern seems to have been to open the way and provide the means for the intellectual development of the blind and to this end he gave his enthusiastic and untiring efforts. Into other philanthropic channels his talents were directed through more than two decades after leaving the Institution. In 1858 he retired from active work, and it is interesting to note that his desire to serve the blind inspired him to spend many years of his leisure in studies such as he had begun while the Superintendent of the Institution.

LABORS OF THE MANAGERS

Whoever follows with curious interest or as a student the history of this organization during the course of three decades from its beginning to the 60's will be struck with the remarkable fidelity of certain of the Managers to the task of conducting the Institution. Chief of these was Dr. Akerly; after him Dr. Isaac Wood, son of Samuel Wood; George F. Allen and Silas Brown, to cite only a few whose long and devoted service deserves more than the brief mention here accorded. Five of the Wood family have been Managers: Samuel Wood, Dr. Isaac Wood, John Wood, Edward Wood and Arnold Wood; the last named great-grandson of the founder being a present member of the Board.

One whose name must always be gratefully remembered for long and intelligent participation in the work of the Institution is Anson G. Phelps, elected a Manager December 30, 1833, made Vice President 1837 and chosen President in succession to Dr. Akerly 1842, serving from 1843 to 1853- A man of great influence in the community, successful in business, a philanthropist, a man of marked piety.

Acceptance of the responsibility of a manager in those days meant actual attention to the details of administration. The minutes of the Board of Managers reveal that the meetings were concerned with every sort of matter: the employment of superintendent and all the intermediates to assistant gardener, the adjudication of matters of discipline and the reprimanding or dismissal of children who were naughty, the procuring of utensils and of food; for example, here is one quotation;:

"The President reports' that a contract had been made with a Baker to bake flour furnished by the institution from twelve shillings per barrel and furnish 280 pounds of bread from each barrel."

The insistent demands of any going concerti for the necessary funds also occupied the time and demanded the personal effort of each Manager. It is not surprising to find that many of those chosen Managers served but a short time, a year or two, and that of the first seventy-five who accepted the office only thirteen endured ten years or more. It was an onerous task and one to be carried on only by truly interested and enthusiastic men.

It was necessary, doubtless, that the detailed management should be thus provided, for the office of Superintendent was filled by a succession of short term incumbents only one of whom continued as long as nine years. After Russ, in twenty years six persons held each for a short period the superintendency. What impress of personality or educational leadership may have been left by these men, save perhaps one, is not revealed in any available records; it is quite impossible that any one, other than such a genius as was Russ, could in two or three years make any impressive contribution. And until the year 1852 no superintendent had had the opportunity to disclose in a published annual report the theory or the practice of his professional sponsorship.

OFFICIAL ACCOUNTING OF STEWARDSHIP

In fact, no reports were published by the Institution until 1837 when the First Annual Report of the Managers was made to the Legislature in obedience to requirement of law, the new organization having been given State aid in the preceding year. This First Report disclosed the steps by which from 1831 through travail of inadequate financial resources and slowly growing public interest the infant Institution had in five years become established and was able to balance its budget. Each of the succeeding Reports, growing steadily in interest to the general reader as the school grew, and the themes were not always the money subject, reflected the devotion of the Managers; presumably the First to the Fourth inclusive are from the hand of Dr. Samuel Akerly. The literary style of the later Reports, as well as their substance, reveals another mind; whose knowledge of the working of the establishment and whose spirit are thus disclosed may be best inferred from the perusal of the Tenth Report, which is signed "Anson G. Phelps, President." Thus it is likely that the voice of the Board of Managers was through all this inchoate period of finding the way, of changing leadership in the school itself, the capable, devoted, responsible President. With the Seventeenth Report,that for 1852, Mr. Phelps made his last contribution to our literature, for in November, 1853, his death occurred.

With the Superintendent's Report prepared by T. Colden Cooper for 1852 the student of the history of the New York Institution finds a beginning of a long series of statements revealing the purposes and ideals of the school as evolved in the mind of the educational leader and his record of its achievements. To this writer it appears obvious that with the six years during which James F. Chamberlain was Superintendent a sense of the importance of having a continuing school policy, directed by the Board's agent, had grown in the minds of the Managers. Mr. Cooper was the first exemplar of this development and he was able to carry out his plans through nine years. His successor, Mr. Robert G. Rankin, occupied the post of Superintendent two years and was followed by William Bell Wait.

SOME PERSONS AND PRACTICES OF THE '40's AND '50's

Concerning James F. Chamberlain, teacher and Superintendent, it should be said that his influence through the years from 1842 to 1852 was probably the chief cohesive element in the school's life. It was a benign influence, as we learn from the testimony of his successor and from a distinguished pupil and teacher, Fanny Crosby. It is to be regretted that there are not available any writings of his authorship by which to measure him.

Through the reports of Mr. Cooper one is given an exposition of the methods of teaching in the classes, the program of studies, the basis in educational theory on which the work proceeded at this stage of progress, the third decade. The writer of these reports reveals himself, particularly in the Seventeenth to the Twenty second inclusive, as an educator of ability to explore and describe the whole problem. There is a spirit of optimism in his pronouncements, though in the discussion of some difficulties he looks them squarely in the face. In particular, there is the problem of the manufactory which the Board for years in its great desire to benefit the adult blind had fostered. This problem had become so acute through the financial losses that disaster to the whole organization threatened. The Superintendent as an educator rightly viewed this as an excrescence which should be removed. (And later it was removed.) It was early in Mr. Cooper's superintendency that the first convention of instructors of the blind was held and the New York Institution was host.

One of the head teachers of this period was William N. Cleveland, who for two years was connected with the school. His interest was temporary, as he was a student of the Theological Seminary, neighbor to the Institution, preparing for the ministry. His younger brother was through his influence employed first in a clerical capacity and later as both secretary and teacher in the literary department. This was Grover Cleveland. The youth who became President of the United States developed in the period of his service, though less than two years, an interest in the welfare of the sightless that he never lost.

In carrying on the task of instruction there seems to have been not only faithful service by teachers of ability but more, a comradeship of mutual assistance in developing a body of methods specially adapted to teaching the blind. That some were actuated by deep religious fervor in this work is undoubtedly true. In selection of teachers the Managers were frequently assured by the committees offering candidates that they were "of excellent Christian character." It was natural that a philanthropy conceived in a community dominated by people of three strong Protestant churches should have a care for religion. And some of the pupils became devoutly engaged in things spiritual.' The most notable instance of this is the case of Frances Jane Crosby, teacher for many years in the Institution, writer of hymns of wide acceptance and use in the 19th century. Contributing to this phase of the influences under which the pupils of the early decades lived was the employment of George F. Root for years as teacher of vocal music, he who became a noted writer of church music. And a contributor to continuity of instruction and holding of the school to excellence of accomplishment was Anthony J. Reiff, music master for twenty-eight years.

From its beginning the New York Institution was committed to the policy of providing manual instruction for its pupils, so much so that in one of the reports of Superintendent Cooper (1853) occurs the comment: "The schools are thus somewhat on the manual labor plan." Skill in manual arts and the manufacture of articles for sale was encouraged and over and over again the authorities of the school petitioned the Legislature for additional support that adult blind people might be employed under the auspices of the Institution. How this was tried and found impracticable is a part of the history that fashioned the later insistence on much training of the hands for physical and cultural effect rather than for industrial purposes.

MEN OF MARK AS MANAGERS

In attempting to complete the picture of the conditions as they were at the beginning of the Wait regime it is quite important for the narrator to introduce some personalities that were to affect the history of the Institution mightily. The President of the Board of Managers with whom he was to begin his association was Augustus Schell, and as President he was to continue through more than twenty years; he had been a member of the Board since 1849; a man of commanding influence. Another member was Alfred Schermerhorn, whose name at once recalls the long-continued devotion of the family to the interests of the Institution. First of this name to become Manager was Peter Augustus Schermerhorn, beginning his service in 1839. A fourth was ' William C. Schermerhorn, who from 1866 to 1901 remained a most devoted friend. His nephew, F. Augustus Schermerhorn, entered on a notable career as Manager in 1870 and for forty years, ten of them as President, gave this school generously his time and interest, besides making special gifts of money for particular needs. The Institution was to him like his child, for there was nothing too much for him to do to advance its interests. At his death half his estate became through his munificence the property of the Institute. A cousin, Alfred E. Schermerhorn, carried on later the tradition and his son, seventh of the name on the roster of Managers, serves today to continue an official interest manifested by this family through most of the century since 1832.

The mention in this connection of others who made possible by loyal support the successful progress of Wait's administration would include William Whitewright, who served longest of any of the Treasurers, a quarter century, Peter Marie, John I. Kane, Frederick W. Rhinelander, Chandler Robbins. These, with others, gave long and faithful support in the years of the school's development to a commanding position in the field of education of the blind.

WILLIAM BELL WAIT

Graduated in June, 1859, from Albany Normal College, William Bell Wait, at 20 years of age, became that same year a teacher in the literary department of the New York Institution for the Blind. At the end of two years he left to study law and was admitted to the bar in 1862. He then became the superintendent of schools of Kingston, N. Y., but was chosen Superintendent of the New York Institution and began his service here October 1, 1863. He was but 24 years old and before him was a task that might well have daunted a man of experience and tried powers.

Graduated in June, 1859, from Albany Normal College, William Bell Wait, at 20 years of age, became that same year a teacher in the literary department of the New York Institution for the Blind. At the end of two years he left to study law and was admitted to the bar in 1862. He then became the superintendent of schools of Kingston, N. Y., but was chosen Superintendent of the New York Institution and began his service here October 1, 1863. He was but 24 years old and before him was a task that might well have daunted a man of experience and tried powers.There was some disorganization in the school, there were financial difficulties to be met, the country was in the darkest time of the Civil War. Undaunted, Mr. Walt took the reins and by his courage, sagacity, knowledge of detail, and indefatigable attention to his duties, he succeeded in securing a firm grip on the discipline of the school, made improvements in the physical property, gained the confidence of the Managers and grew steadily into that superb command of himself and which he became noted. He doubtless had no sense of his true importance at this time; he did not realize in the affairs of the Institution he was the leader in a new era. Rather, a found a piece of work to be done and he began to do it with all his might.

PROGRAM AND PERFORMANCE

Whoever reads the annual reports of the Superintendent from 1863 to 1904 will come to realize that he is virtually pursuing an inquiry into the history of education of the blind in America. Each year Wait gave evidence of his industry in exploring the field and of his intelligence in dealing with the problems presented. Investigation of conditions in the State as respects the blind, consideration of causes of blindness, presentation of the facts-all these prefaced announcements of policy and purpose in shaping the work of training the youth. The contrast between this, the scientific method, and armchair philosophizing on what ought to be and therefore is, appears most marked in these progressively valuable papers in the education of the young blind. So the New York Institution became steadily more influential in its proper field. And without faltering the presiding genius went on with his determined course to exalt the intellectual. He saw the value of music as mental discipline as well as for esthetic training. Fortunately as he entered on his work in 1863 there had been employed a young German, Theodore Thomas, as successor to Anthony Reill in the music department, and this genius gave valued aid in setting high standards and exalting the place of music in the training of the blind. The Institution thus enjoyed for a number of years the services of a man whose prestige grew to be nation. and worldwide; his qualities influenced the setting up of music of highest grade as a distinctive part of the school's program.

The need for definite instruction in physical development, the establishment of a definite course of studies in music as well as in literary subjects, a call for character training in schools, an analysis of qualifications of the teacher‑these are some of the subjects which in these Reports are presented and discussed in a most scholarly fashion.

PRINTING FOR THE BLIND

Early in his career Mr. Wait was impressed with the need for improved facilities whereby pupils could both read and write. In 1866 appeared his scientific analysis of the situation, a world of the blind using variously approved forms of embossed literature, chiefly "raised letters," with a few accepting the dots of Braille; and because the dot system could be used for writing as well as for making books, he gave his influence for general adoption of Braille's system. There was little agreement and his further study led to a proposal for a less cumbersome system, having many advantages over that of Braille, which was called the New York System. These studies and discussions occupied much of the time of the busy Superintendent, who nevertheless was able to carry forward improvements in the buildings and provide for more and more pupils, manage the factory part of the establishment, and progressively relieve the Board of Managers of intimate direction of the minutia of an institution's affairs. In 1868 were printed the signs used in the system destined to be known as New York Point, and a report of tests carefully conducted with pupils to ascertain its value. In concluding the presentation Mr. Wait acknowledges his indebtedness to Mr. Stephen Babcock, the blind principal teacher, for assistance the man who through fifty years of service made valuable contributions to the success of the school and presents the system to the judgment of the world of education of the blind.